Pragmatism

In this Sinology, Andy Rothman addresses key investor questions and explains why he’s gone from being cautiously optimistic about Xi returning to pragmatism, to now being bullish on the Chinese economy.

Subscribe NowI have long argued that China has become rich and the Communist Party—including under Xi Jinping—has stayed in power because of pragmatic economic and social policies. I’ve also noted that over the last three decades, the Party—including under Xi—has often made poor policy choices, but has usually changed course to a more pragmatic path. Recently, Xi has returned to a more pragmatic approach to the property market, to regulatory policy, to entrepreneurs, and to Washington. On November 11, with his decision to end his zero-COVID policies, Xi also took a more pragmatic approach to the pandemic.

These decisions by Xi signal that he understands that pragmatism is the best course for his country’s future, and for his own legacy. By the second quarter of this year, this return to pragmatism should result in a domestic demand-driven economic recovery, fueled in part by a drawdown of the massive accumulation of household bank deposits since the start of the pandemic. With Beijing likely to remain the only major government engaged in serious easing of fiscal and monetary policy—while much of the world is tightening—China may once again be the engine of global economic growth.

I know that investors have concerns and questions about the sustainability of Xi’s recent policy course corrections, about risks to growth from structural problems in the property market, as well as about political risks from rising tensions across the Taiwan Strait and the Pacific Ocean. In this Sinology, I address those questions and explain why I’ve gone from being cautiously optimistic about Xi returning to pragmatism, to now being bullish on the Chinese economy.

Why did Xi abandon zero-COVID and take the more pragmatic approach of living with the virus, like the rest of the world?

Zero-COVID worked well prior to the arrival of Omicron. There were very few deaths in China, and the economy was strong. In 2021, consumer spending, the largest part of the economy, was up more compared to 2019 than in the U.S. and the Euro area. Manufacturing was healthy and China held up its end of global supply chains.

After Omicron arrived, zero-COVID continued to be successful from a public health perspective, but the economic and social cost was disastrous. Fear of lockdowns made families and companies reluctant to spend. Growth slowed and unemployment rose, especially among young people. Under zero-COVID, China’s economy was on an unsustainable path. Additionally, later variants of the virus were so transmissible that lockdowns were no longer an effective response.

Xi’s course correction away from zero-COVID was not unexpected. Last April, I wrote that, “Over the last three decades, Beijing has often made poor choices, but has usually changed course to a more pragmatic path, and I expect that to happen again.” In October, I wrote, “The most important decision Xi has to make—and soon—is about his COVID-mitigation policies, which are slowly strangling China’s economy. . . I’m confident, however, that the Chinese government will return to a more pragmatic approach, which strikes a better balance between public health and the economy.”

Xi made that decision on November 11, when his government published a list of 20 measures designed to “optimize” mitigation of COVID, marking a significant change in direction of policy towards living with the virus and away from zero tolerance for cases. This was prior to the public protests, which accelerated implementation of the policy changes.

COVID seems to be running wild across China. Will this become a public health disaster?

The first, massive COVID outbreak in China “probably peaked in late December, according to a preliminary analysis on the number of infections late last year and data on travel between cities,” reported the journal Nature, on January 16. The article cited analysis by an infectious-diseases modeler in the UK, who found that “close to half of China’s cities experienced a peak in infections between 10 December and 31 December. For a further 45% of cities, the peak is predicted to occur in the first half of January.”

A senior public health official in China said on December 21 that more than 250 million people, about 18% of the population, had already been infected in the first 20 days of December, and that more than half of residents of larger cities had been infected. In early January, a public health official in Henan, the third most populous province, said that nearly 90% had been infected, including in rural areas. These estimates are probably drawn from online surveys that local health officials are conducting across the country.

This is consistent with data showing a significant recovery in activity across urban China, including subway and freight traffic. Our friends in China report that in recent weeks, traffic jams and lines at popular restaurants have returned.

The transition to living with COVID has, of course, been painful for many, and while China’s National Health Commission reported on January 14 that about 60,000 people had died due to COVID since December 8, that number only covered people who died in a hospital, so the true count was undoubtably much higher. But, while opening up has been a shock to China’s health care system, it has not resulted in the public health disaster that some had feared.

The next risk will come from the huge movement of people across the country during the lunar new year holiday which begins on January 22, when there may be a spike in cases in rural areas, where the health care system is weaker. The health impact of this holiday travel should be clear by late February.

How bad was China’s economy in 2022?

China’s economy was in terrible shape last year. The upside is that this led Xi to change course on everything from zero-COVID to his policies on property and tech regulation, which should set the stage for far better economic performance this year.

The impact of Omicron and lockdowns led China to record its second-slowest GDP growth rate since the reform and opening period began in 1979. 3% growth in 2022 was down from 6% in pre-COVID 2019, although the 2.2% pace of 2020—the first year of the global pandemic—was even worse.

Another way to put last year in context is that the net increase in nominal GDP was 6.1 trillion renminbi, equal to 91% of the nominal increase in 2019. Nonetheless, last year, China’s GDP expanded by an amount greater than the size of Saudi Arabia’s 2021 GDP.

After the terrible economic data from last year, will Chinese consumers be ready to spend again?

I’m optimistic about the Chinese consumer. The change in COVID policy has been accompanied by new government measures to support recovery of the property sector in what appears to be a coordinated effort to restore consumer confidence and jumpstart one of the most important parts of the economy.

As the impact of zero-COVID and the first wave of COVID cases recede, I expect hiring and job security to improve, which should lead to stronger income growth, allowing consumer confidence to gradually bounce back to pre-pandemic levels.

At the same time, China is likely to remain the only major economy engaged in serious financial easing, while much of the world is tightening.

Stronger consumer confidence is then likely, in the second quarter, to lead families to begin drawing down the massive amount of extra savings from the zero-COVID period.

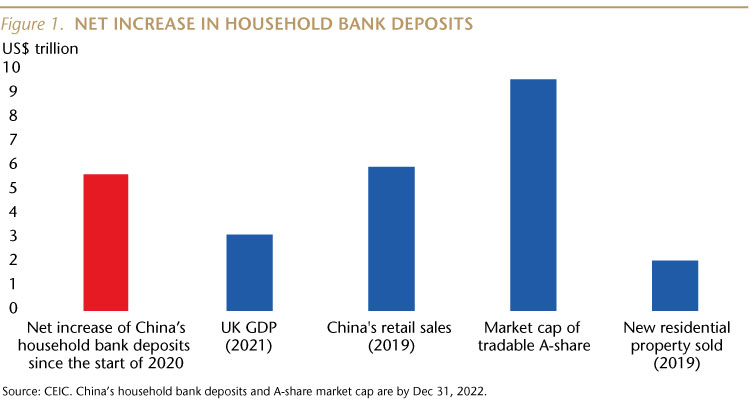

Chinese households were in savings mode during zero-COVID, with family bank balances up 48% from the start of 2020. The net increase in household bank accounts is equal to US$5.6 trillion, which is larger than the GDP of the UK in 2021, and equal to 96% of China’s 2019 retail sales. This is significant fuel for a consumer spending rebound, as well as a continued recovery in mainland equities, where domestic investors hold about 95% of the market.

With the world slowing down, China’s exports have begun to weaken. Will that prevent China’s economic recovery?

In recent months, the global economy has slowed, putting the brakes on China’s export growth. That trend is likely to continue, but this will have only a modest impact on the overall Chinese economy, which is driven primarily by domestic demand.

Last year was the 11th consecutive year in which the services and consumption (tertiary) part of China’s GDP was larger than the manufacturing and construction (secondary) part, as rebalancing continued despite the pandemic. Exports were unusually strong during much of the COVID era but are gradually returning to their pre-pandemic levels.

During the five years through 2019, net exports—the value of a country’s exports of goods and services minus its imports—on average contributed zero to China’s GDP growth each year.

Two other trade trends are worth noting. First, the share of China’s trade undertaken by privately owned firms exceeded 50% of the total last year, up from a 28% share in 2011, the year before Xi became Party chief.

Second, talk of a trade war and additional tariffs on Chinese goods meant that the share of China’s exports which went to the U.S. last year declined to 16.2% of the total, down from a 19% share in 2017, prior to the tariffs. Still, China’s share of global exports rose to 14.6% as of the third quarter in 2022, up from a 12.8% share in 2017.

"Why do I believe Xi supports small businesses? Because entrepreneurial, privately owned companies drive creation of jobs, innovation and wealth in China. The government depends on these companies."

In his October Party Congress speech, didn’t Xi attack entrepreneurs?

I’m aware that many commentators described Xi’s work report to the Party Congress as belligerent and focused solely on national security and political control. But, after reading the 64-page speech, I’m puzzled by those assessments.

Xi said he is “focused on promoting high-quality development” and that he wants to “bring per capita disposable income to new heights” and “substantially grow the middle-income group as a share of the total population.” He said, “development is our Party’s top priority,” and that “we will provide an enabling environment for private enterprises.” He pledged to “raise total factor productivity.”

In January, Vice Premier Liu He said, “Some people say China will go for the planned economy. That’s by no means possible.”

Why do I believe Xi supports small businesses? Because entrepreneurial, privately owned companies drive creation of jobs, innovation and wealth in China. The government depends on these companies.

Has Xi become more pragmatic on property, and is this enough to overcome the structural problems?

The residential property market was very weak last year. New home sales declined 26.8% on square meter basis compared to 2021, while average new home prices fell 2%. This weakness was, however, the result of two government policies. First, zero-COVID lockdowns, which left consumers worried about job and income security. Second, a series of policies designed to stress over-leveraged developers and promote consolidation in a very fragmented industry, but these policies were overdone and damaged homebuyer confidence.

Zero-COVID is over, and I expect consumer confidence to recover in the coming months. And, the government has revised the most damaging property policy, the “three red lines” regulations that limited developer access to financing. Xi also announced in November his intention to reverse several policies that had effectively shut down the residential property market. He endorsed new measures which encourage banks and trust companies to extend maturity for construction financing, as well as support for bond issuance by privately owned developers, both of which should improve cash flow and project completion. Government-directed banks have also cut average mortgage rates by 137 basis points (1.37%) since the start of 2022, and mortgage processing time has been reduced.

I’m not very worried about the overall structure of China’s residential property market. It’s not a bubble. Bubbles are all about leverage, and homeowner leverage is much lower in China than in the U.S. In China the minimum cash down payment for a new flat is 20% of the purchase price, and the average is 30% down. Far from the median cash down payment of 2% ahead of the U.S. housing crisis. And, surveys tell us that about 90% of new homes in China are sold to owner-occupiers. With average new home prices up 34% over five years and 88% over 10 years, prices are not signaling the existence of ghost cities.

The pragmatic course correction should lead to a gradual, steady recovery in new home sales in the second half of 2023.

Is Xi really becoming more pragmatic about the tech sector?

Xi’s government made a lot of mistakes over the last couple of years, especially in regulation of the tech sector, but they’ve acknowledged this and have promised to be less disruptive. Why do I believe them? Because as I noted earlier, entrepreneurial, privately owned companies drive creation of jobs, innovation and wealth in China. The government depends on these companies. And I think the government’s "common prosperity" policy objectives are admirable: they are focused on the same inequality problems we are wrestling with in our countries.

In a December speech, Premier Li Keqiang signaled a lighter regulatory approach towards on-line platform companies. “The platform economy has promoted consumption and employment,” Li said, adding that the government “supports the healthy and sustainable development of the platform economy.”

Li’s signal was amplified later that month by the Central Economic Work Conference, chaired by Xi, which declared that the government “must vigorously develop the digital economy” and “support platform companies in leading development [and] creating jobs.”

In January, Li reiterated support for “the healthy and sustainable development of the platform economy,” and another senior official said the regulatory overhaul of the 14 major platform companies “has basically been completed, and a few remaining issues are also being solved.”

Isn’t Xi’s leadership team packed with “yes-men” who will be afraid to speak truth to him?

The consensus take on the new leadership lineup announced at the October Party Congress is that they are all yes-men, who will be afraid to disagree with Xi. The Politburo Standing Committee—the top leadership of the Chinese Communist Party—is packed with Xi supporters, but that doesn’t mean they won’t advocate for the pragmatic approach that served the Party well in the past. Li Qiang, who is second in command, spent almost 40 years working in China’s most economically dynamic and entrepreneurial province, Zhejiang (home to Alibaba), so he is well familiar with the importance of private companies to the success of the economy and the Party.

It is possible that a leadership team handpicked by Xi will have greater freedom to offer constructive criticism and challenge his ideas—because Xi trusts that they do not represent a political threat. The early days after the Congress—which included significant changes to policy on COVID, on property, on tech regulation and on relations with Washington—suggest that this is not a team of yes-men.

Is Xi planning to attack Taiwan?

I’m not very worried about China invading Taiwan. The military risks are huge. Crossing 100 miles of sea would be far more difficult than Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. And the economic impact would be disastrous. China imports over 80% of the semiconductors it consumes, with about one-third—including all of the most sophisticated chips—coming from Taiwan. This supply would be cut off if there were signs that Beijing planned an attack, crippling China’s economy. There are no signs that China is preparing to use force.

After meeting with Xi in Bali in November, Biden said, “I do not think there’s any imminent attempt on the part of China to invade Taiwan.” On January 11, the U.S. Secretary of Defense made similar remarks.

In Washington, there seems to be a bipartisan agreement to be tough on China. Is Xi really going to respond in a pragmatic way?

I believe U.S. – China relations will remain tense, but conflict, including over Taiwan, will be avoided.

When Xi and Biden met in Bali in November, both made serious efforts to put a floor under the rapidly sinking bilateral relationship.

I do not expect U.S. – China relations to improve significantly, in large part because of domestic politics in the U.S., but the odds of further deterioration were reduced as a result of their first in-person meeting since Biden was elected president.

After the meeting, Biden said, “I absolutely believe there need not be a new Cold War,” and he said about Xi, “I think that we understand one another.”

In response to a reporter’s question, Biden said, “And do I think he’s willing to compromise on various issues? Yes.”

Since Bali, Xi has also taken steps to signal a desire to improve relations with the U.S. He promoted his ambassador in Washington to become foreign minister, and he demoted one of the most visible “wolf warrior” Chinese diplomats. Dialogue between senior officials of both governments has increased in recent weeks and more meetings are scheduled. Treasury Secretary Yellen and Secretary of State Blinken have both announced plans to visit Beijing.

It is also very positive that the long-running dispute over audits of accounting workbooks for Chinese companies listed in the U.S. was resolved in December. The chair of the U.S. Public Company Accounting Oversight Board announced that American “investors are now more protected because the PCAOB has been able to inspect and investigate audit firms in mainland China and Hong Kong completely.”

This agreement goes beyond keeping 200 Chinese companies trading in the U.S. It signals a desire, in my view, on the part of Xi, to avoid economic decoupling with the U.S., and to steady his relationship with Biden.

China’s getting old. Won’t that get in the way of an economic recovery?

China’s workforce is shrinking, and its population is aging, but this is a long-term issue: China won’t be as old as Japan is today until 2050. And, Beijing is taking steps to mitigate a declining workforce. A better educated population, for example, to help manufacturing move up the value chain. The number of university graduates rose 60% over the last 10 years. Additionally, government spending on health care has almost tripled over that time.

A pragmatism-driven recovery is likely

In this Sinology, we’ve explained that recent policy course corrections by Xi Jinping signal that he understands that pragmatism is the best course for his country’s future, and for his own legacy. By the second quarter of this year, this return to pragmatism should result in a domestic demand-driven economic recovery, fueled in part by a drawdown of the massive accumulation of household bank deposits since the start of the pandemic. With Beijing likely to remain the only major government engaged in serious easing of fiscal and monetary policy—while much of the world is tightening—China may once again be the engine of global economic growth.

Andy Rothman

Investment Strategist

Matthews Asia